Yet Another Eclipse for Herod

Reprinted from The Planetarian*, vol. 19, no. 4, Dec. 1990, pp. 8-14.

©1990 by John P. Pratt. All rights Reserved.

| This paper proposes yet another eclipse as the correct choice: that of December 29, 1 B.C. It also suggests that Christ was born at the Passover season of 1 B.C. and discusses compatibility with traditional Christmas dates. |

| 1. Evidence for 4 B.C. |

| 2. Problems with 4 B.C. |

| 2.1 Christ About 30 |

| 2.2 Impossible Month |

| 2.3 Empire-wide Registration |

| 2.4 Governor in 6-5 B.C. |

| 2.5 Evening eclipse |

| 3. A.D. 1 Explains All Evidence |

| 3.1 Evidence for 1 B.C. |

| 3.2 Gaius Caesar |

| 3.3 Herod’s Successors |

| 3.4 Colonia Julia |

| 3.5 Josephus’ Chronology |

| 4. Was Christ born in 1 B.C.? |

| 4.1 Age Thirty |

| 4.2 Passover Birth |

| 4.3 2 B.C. Conjunction |

| 4.4 Star of Bethlehem |

| 5. Traditional Dates |

| 5.1 Anno Domini |

| 5.2 December 25 |

| 5.3 January 6 |

| 6. Conclusion |

| Notes |

The date of the reported lunar eclipse shortly before the death of King Herod has long been recognized to be important for delimiting possible dates for the birth of Christ. For many years it has been believed that the eclipse occurred on March 13, 4 B.C., and hence that Christ must have been born about 6-5 B.C. However, recent re-evaluation has raised questions about that eclipse, and two other dates have been preferred: Jan. 10, 1 B.C.,[1] and Sept 15, 5 B.C.[2] This paper proposes yet another eclipse as the correct choice: that of December 29, 1 B.C. It also suggests that Christ was born at the Passover season of 1 B.C. and discusses compatibility with traditional Christmas dates.

1. Evidence for 4 B.C.

The principal source for the life of Herod is the works of Josephus, a Jewish historian who wrote near the end of the first century. His methods are not always clear and he is sometimes inconsistent so care must be exercised to cross-check his chronology with other sources. Events that are also dated in Roman history are usually the strongest evidence to correlate his history with our calendar. Josephus states that Herod captured Jerusalem and began to reign in what we would call 37 B.C., and lived for 34 years thereafter, implying his death was in 4-3 B.C. Other evidence both from Josephus and coins indicates that his successors began to reign in 4-3 B.C. Moreover, Josephus also mentions a lunar eclipse shortly before Herod’s death.[3] For centuries the evidence from astronomy has appeared decisive: a lunar eclipse occurred on March 13, 4 B.C., whereas there was no such eclipse visible in Palestine in 3 B.C. Thus, the eclipse has played a crucial role in the traditional conclusion that Herod died in the spring of 4 B.C.

2. Problems with 4 B.C.

2.1 Christ About 30

Luke says Christ “began to be about thirty years of age” shortly after John the Baptist began his ministry in A.D. 29 (Luke 3:1,23).[4] Because that would put his birth about 2 B.C., Filmer[1] proposed the Jan. 10, 1 B.C. eclipse for Herod. His treatment of the historical evidence, however, was faulty,[5] so the problem remained unsolved.

2.2 Impossible Month

So many events are recorded by Josephus[6] as occurring after the eclipse and before the following Passover, that it appears impossible (or extremely unlikely) that they all occurred in only 30 days, as required by the 4 B.C. scenario. Each of these events probably took at least a week:

- Herod’s sickness increased; part of his body putrefied and bred worms.

- He was taken at least ten miles to warm baths and returned when treatment failed.

- He ordered important men to come from every village in the nation (up to 70-80 miles); they arrived.

- Herod’s son Antipater was executed and Herod died five days later (on or after the first day of his 34th regnal year, probably March 29, if in 4 B.C.).

- A magnificent funeral was planned and held for Herod, whose body was carried about 23 miles and then buried.[7]

- A 7-day mourning began, followed by a funeral feast.

- Another public mourning was planned and held for the patriots who had been executed during the day preceding the night of the eclipse.[8]

Such time considerations led Barnes to prefer the Sept. 15, 5 B.C. eclipse.[2] Martin, who has discussed many problems with 4 B.C. at length,[9] has pointed out that such a date is far too early; Herod’s son Archelaus would never have delayed until after the next Passover to go to Rome to confirm his kingship.

2.3 Empire-wide Registration

Until recently, no empire-wide enrollment (Luke 2:1) was known that would have been required of Joseph and Mary; the commonly cited taxation of 8 B.C. applied only to Roman citizens. Now Martin has identified it as a combined census and oath of allegiance to Augustus in 3-2 B.C., perhaps related to the bestowal of the title “pater patriae” (father of thy country) by the senate on Feb. 5, 2 B.C.[10] Josephus records that over 6,000 Pharisees refused to pledge their good will to Caesar (about a year or so before Herod died),[11] probably referring to that oath because the census would have recorded how many refused. Orosius (a fifth century historian) clearly links an oath to the registration at the birth of Christ:

“[Augustus] ordered that a census be taken of each province everywhere and that all men be enrolled. So at that time, Christ was born and was entered on the Roman census list as soon as he was born. This is the earliest and most famous public acknowledgment which marked Caesar as the first of all men and the Romans as lords of the world … that first and greatest census was taken, since in this one name of Caesar all the peoples of the great nations took oath, and at the same time, through the participation in the census, were made part of one society.”[12]

He identified the time of the census using two Roman systems that both agree to indicate 2 B.C.[13] This implies a lower limit for Herod’s death of 2 B.C.

2.4 Governor in 6-5 B.C.

Josephus says that Varus was governor of Syria at Herod’s death and Varus is indeed indicated as such in 4 B.C. by coins.[14] The problem, pointed out by Martin, is that the coins also show Varus was governor in 6 and 5 B.C., whereas Josephus indicates that Saturninus was governor for the two years preceding Herod’s death.[15] Martin’s solution is that an inscription found near Varus’ villa, which describes a man who was twice governor of Syria, probably refers to Varus. If so, his second term could well have been about 1 B.C., when there is no record of anyone else as governor.[16] Like Filmer, Martin chose the Jan. 10, 1 B.C. eclipse which also solves the “impossible month” problem, but it suffers (along with the March 13, 4 B.C. eclipse) from the following problem.

2.5 Evening eclipse

Why was Herod’s eclipse the only eclipse mentioned by Josephus in his lengthy histories? A partial answer is that it occurred on the night after the execution of some Jewish patriots, and would probably have been interpreted as a sign in heaven related to their death. However, with lunar eclipses visible in Palestine every year or so, it seems strange that others are not mentioned. If Josephus had access to records of such observations, surely he would have included at least some other eclipses which coincided with historical events. It is unlikely that the execution date was chosen for dramatic impact because Herod had the offenders executed very soon after they had been apprehended. So why did Josephus include Herod’s eclipse but no others?

An obvious answer is that the eclipse was widely observed and then associated with the executions. If so, then the eclipse occurred in the early evening. Using this criterion, the eclipses of March 13, 4 B.C. and January 10, 1 B.C. are extremely unlikely because they both began the umbral phase more than six hours after sunset and hence would have only been seen by at most a few people. The eclipse of Sept 15, 5 B.C. began three hours after sunset, but that is also late.

|

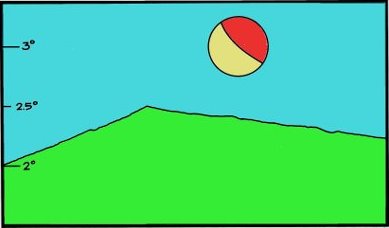

On the other hand, the eclipse of December 29, 1 B.C. fits this criterion very well. The full moon was nearly half eclipsed when it could first be seen rising in the east above the distant mountains about twenty minutes after sunset (See Fig. 1). It would not have been seen much before that time, even without the mountains, due to sky brightness.[17] At first the eclipsed half of the full moon would have been invisible, then it would have appeared dimly lit, and finally the characteristic reddening of the eclipsed portion would have become noticeable. The umbral phase continued for about an hour after first visibility. Note that a partial eclipse is more easily seen at moonrise than a total because totality delays first visibility (the entire moon is in the “invisible” portion) and the shape of the missing portion would have made it obvious that it was an eclipse, especially to the Judeans who used the moon to indicate the day of the month and who expected a full moon. Of the candidates to be Herod’s eclipse, the December 29, 1 B.C. eclipse was the most likely to have been widely observed

If December 29, 1 B.C. is correct, then Herod died in early A.D. 1 rather than early 1 B.C. In the next section, this paper discusses how an A.D. 1 death date for Herod might explain all of the historical evidence.

3. A.D. 1 Explains All Historical Evidence

3.1 Evidence for 1 B.C.

The proposed date of A.D. 1 fits all of the evidence indicating Herod’s death was about 1 B.C. It allows Christ to have been born during the census begun in Judea in 2 B.C. and hence to be about 30 in A.D. 29, both in agreement with Luke’s account. It also allows an ample three months for all the events that would not fit into one month in 4 B.C. Moreover, it fits the arguments Martin has made concerning the second governorship of Varus, uprisings in the Roman empire in the east beginning in 1 B.C., and the awarding of an imperial acclamation in A.D. 1 or 2[18], because all of those events would fit well in either A.D. 1 or 1 B.C.

3.2 Gaius Caesar

One of the arguments against a 1 B.C. death date for Herod is that Josephus states that Gaius Caesar was in Rome after Herod’s death, whereas Roman sources state that Gaius was sent in 1 B.C. to the east to squelch a revolt of the Parthians and others.[19]

An A.D. 1 date for Gaius to have been found in Rome, however, fits better. Gaius became one of the two consuls of the Roman empire, beginning his term on January 1, A.D. 1. Normally the consuls resided in Rome, but because of the unsettled conditions, Gaius was stationed in Syria. According to the Roman historian Dio Cassius, Gaius made peace in early A.D. 1 with Phrataces, king of Parthia. He says, “Nevertheless, war did not break out with the Parthians, either. For Phrataces, hearing that Gaius was in Syria, acting as consul … forestalled action on their part by coming to terms with the Romans…”[20] The relatively peaceful interlude that followed would have been a natural time for Gaius to return to Rome, even if only for a short visit.[21] In A.D. 2, the Armenian war began in which Gaius was wounded; he died in A.D. 4.

Thus, A.D. 1 presents a more plausible scenario than 1 B.C. for Gaius to have been in Rome after Herod’s death.

3.3 Herod’s Successors

If Herod died in A.D. 1, why did his sons Archelaus, Antipas and Philip reckon their reigns from 4-3 B.C.? The best answer seems to be Martin’s: Herod’s sons reckoned their reigns from the beginning of his son Antipater’s regency with him about 4 B.C., which began either when Antipater was named heir to the throne or later at the death of Herod’s two royal sons. One clue that the latter may be the best choice is that Josephus begins many books at the death of a king (marking the beginning of the next king’s reign) and he begins Book XVII of Antiquities with the death of the royal sons. Herod was the only king until the day he died, but he let Antipater rule with him and handle many of the public affairs.[22] Antipater did not continue in that regency but went to Rome, and he died before Herod, but had he survived, he may well have counted his regnal years from the beginning of his regency under Herod. After Herod’s death, Antipas replaced the former tetrarch of Peraea and might have dated his reign from his death in 2-1 B.C. (shortly after the oath of allegiance).[23] Not to be outdone, Archelaus could have reasoned that he was really continuing the reign of his brother Antipater, which began in 4 B.C. Finally, to maximize their reigns, all three successors might have all adopted that rationale to justify antedating their reigns.

One argument against this antedating proposal has been that the successors did not actually reign before Herod’s death, but that is not the point. The question is whether or not they did, in fact, antedate their reigns. The earliest coins known for any of the successors’ reigns is for “year 5,” which is consistent with the antedating theory that A.D. 1, their first de facto year, was their fourth or fifth year de jure. Another apparent argument against antedating has been that Herod’s son Philip built a capital city named Paneas, which second and third century coins imply was founded in 3 B.C. That founding date, however, is easily explained as simply being the first year of Philip’s antedated reign.[24]

3.4 Colonia Julia

Apparently the only other argument against the antedating theory concerns a village that Philip built into a city and renamed Julia. Josephus notes that it had the same name as Augustus’ daughter and Barnes argued that this name must have been given before 2 B.C. when she was banished. This argument, however, is based on an apparent misunderstanding by Josephus. Many Roman colonies were begun throughout the empire named Colonia Julia (or simply Julia), meaning “Julian Colony.” They were named for the Julian (as in Julius Caesar) emperor (Augustus). Another similar example of a feminine name is the fortress Antonia which Herod named for Mark Antony. Josephus also thought that another city named Julia must have been named after Augustus’ wife, the mother of Tiberius, but her name was Livia and she was not known as Julia.[25]

3.5 Josephus’ Chronology

Could Josephus not have known that Herod’s sons antedated their reigns? That is entirely possible because he knew very little about their reigns. He devoted only one verse in his Antiquities to the ten years of Archelaus and only two more to the first thirty years of Antipas and Philip,[26] whereas Herod’s reign required thirty chapters.

Josephus only gives two Roman years during Herod’s entire reign: 40 B.C. when he was named king by Rome, and 37 B.C., when he took Jerusalem and had the reigning king killed.[27] Josephus then dates events with the year of Herod’s reign, as if it were obvious which of the two starting points is implied. And perhaps it should be obvious. The custom was to reckon from the death of the former king, which implies 37 B.C.; moreover, Josephus begins a book in his Antiquities with the death of the former king in 37 B.C. The conclusion that Herod’s first year began in 37 B.C. is confirmed by events from Roman history: Augustus’ defeat of Antony in 31 B.C. was in Herod’s seventh year and the expedition of Gallus in 24 B.C. was in Herod’s fourteenth year.[28]

At Herod’s death, Josephus says that Herod reigned 34 years from the death of the former king, but then adds that he had reigned 37 years counting from the 40 B.C. date.[3] Why did Josephus suddenly reckon from 40 B.C. for the first time? And if Josephus had access to a detailed history of Herod, how could he be wrong about the length of Herod’s reign?

As a possible answer to both questions, suppose Josephus’ source said Herod reigned 37 years (consistent with his death having been in early A.D. 1). Because other records implied that Herod’s successors reckoned their reigns from 4-3 B.C., he would have seen an apparent conflict because they began to reign at Herod’s death. Faced with this dilemma, he might well have decided that the best solution was that Herod’s 37 years must have been counted from 40 B.C. This explains both why he would have incorrectly assigned 34 years to Herod’s reign as well as why he added the new reckoning from 40 B.C. in order to use the “37 years” from the original source.[29]

Thus, it is concluded that Herod died in A.D. 1 because the Dec. 29, 1 B.C. eclipse was the most likely, it explains all of the historical evidence, and it’s easy to see how Josephus could have made his mistakes. This conclusion does not require that the birth of Christ also be later, but it does allow that possibility.

4. Was Christ born in 1 B.C.?

4.1 Age Thirty

As mentioned above, Luke says Christ was about thirty when he was baptized after John began his ministry in A.D. 29. The year of A.D. 29 is also indicated because the crucifixion of Christ most likely occurred in the spring of A.D. 33[30] (with A.D. 31 and 32 astronomically unacceptable), and the Book of John implies that his baptism was about three and a half years before.

If Christ was baptized in A.D. 29, one needs only to count back “about thirty” years to arrive at his birth date about 2 B.C. Today it is popular to interpret “about thirty” as meaning “26-34” in order to accommodate a birth date for Christ in 6-5 B.C. However, the early Christian fathers, such as Irenaeus and Epiphanius, accepted the straightforward interpretation that it meant a few months less than thirty.[31]

Christ made a point of fulfilling the law of Moses in every detail (Mat. 5:17), which would have included beginning his public ministry at age 30 (Num. 4:3). He apparently began his public ministry at the Passover in A.D. 30 (after his baptism) because 1) his first miracle was done rather secretly “not many days” before that Passover (John 2:9-13); 2) at that time he said, “mine hour is not yet come” (John 2:4), suggesting that the time for his public ministry had not arrived because he was not yet thirty; and 3) he then openly taught and did miracles at Passover (John 2:23),[32] implying that he was then thirty. If so, Christ was born in the spring of 1 B.C., on or shortly before Passover.

4.2 Passover Birth

A Passover birth for Christ is likely for other reasons. It has already been noted that spring was lambing season when shepherds watched their flocks by night (Luke 2:8), that it would fit the timing of Gabriel’s visit to Zacharias (Luke 1:5-13), and that it would explain the crowded inn (Luke 2:7) if his birth was during Passover.[33] This last argument is especially strong because a registration that lasted at least several months would hardly have crowded Bethlehem at any time. On the other hand, Joseph, like all Jewish men before the destruction of the temple, was required to go to Jerusalem for Passover (also Pentecost and Tabernacles, Deut. 16:16), even with Mary so near to giving birth. It would have been logical to visit nearby Bethlehem to register to save making a special trip from Nazareth. The crowdedness suggests that Christ was born at most a day or so before Passover, because travelers would not need to arrive many days early.

The birth of Christ in 1 B.C. fits the 2 B.C. timing of the enrollment described by Orosius very well. He assumed that Christ was born in the year the decree was made (2 B.C.), but Luke says the decree was made “in those days” (Luke 2:1), referring back to when John the Baptist had been born about six months earlier in 2 B.C. (Luke 1:26).

| Thus, it is proposed that Christ was born on, or a day or so before, the Passover of 1 B.C. |

Thus, it is proposed that Christ was born on, or a day or so before, the Passover of 1 B.C. The day of the Passover sacrifice most likely fell on Thursday, April 8, 1 B.C. The latest day for his birth would be April 9, the Passover feast day, by which he had begun preaching in A.D. 30 (John 2:23). This would mean Christ was born about April 6-9, 1 B.C. on the Julian calendar. Note that the Julian calendar had not been properly implemented, so the day that should have been called April 8, 1 B.C. was actually called April 7;[34] moreover, on our (Gregorian) calendar it would be called April 6. To avoid confusion, this paper uses the usual Julian calendar notation.

4.3 The June 17, 2 B.C. Conjunction

Many conjunctions in the 3-2 B.C. skies have been noted that might have been interpreted by the magi as being signs of the birth of Christ,[35] but one far excels the others as being truly outstanding. The conjunction of Jupiter and Venus on June 17, 2 B.C. was so close that the two planets would have appeared to touch each other. Calculations indicate that there has never been a brighter, closer conjunction of Venus and Jupiter so near to the bright star Regulus in Leo in the 2000 years before or since.[36]

It is hard to know how the magi might have read “signs” in the heavens, but it has been noted that Jupiter/Zeus was the father god and was often associated with the birth of kings, that Venus was the mother, or goddess of fertility, and that Leo, with the bright king-star Regulus, was the “king” constellation associated with Judah and royalty.[37] Thus, this combination seems to be a natural to be interpreted as the coming of the “King of the Jews” (Mat. 2:2).

It has also been noted that when the two planets “fused into one”[38] they would have appeared to be in a “marriage union” with each other.[39] Associating that conjunction with the time of the conception of Christ not only fits his proposed birth in 1 B.C., it also dovetails with two ancient traditions mentioned by the fourth century Christian father Epiphanius. First, he held that the conception of Christ occurred on June 20, which is very close to the June 17 conjunction. Secondly, he also noted a tradition that the pregnancy lasted ten months,[40] which is a perfect fit because the conjunction occurred near the full moon ten lunar months before the following Passover.

4.4 Star of Bethlehem

If this conjunction occurred near the time of conception,it may have been part of a series of signs that were recorded simply as a star (Mat. 2:9).[41] Note that the magi found Jesus at Bethlehem, which means they probably arrived within 50 days of Jesus’ birth because Joseph and Mary would have stayed in Bethlehem that long to present Jesus at the temple after 40 days (Luke 2:22) and to attend Pentecost after 50 days, but then would have returned to Nazareth. Yet Herod slew the infants from two years and under according to the time the star had appeared (Mat. 2:7,16). Why two years, if the star had appeared less than two months before? It seems to imply that the magi mentioned a sign of the conception and Herod was making sure they had not mistaken the birth for conception. The proposal that Christ was born at Passover of 1 B.C. is also compatible with other traditional dates for his birth date, as will now be discussed.

5. Traditional Dates for the Birth of Christ

5.1 Anno Domini

The sixth century scholar Dionysius Exiguus determined the Christian era (A.D.) based on his calculation of the year Christ was born (1 B.C.). If Christ was really born about 6 B.C., how can such a large error be explained, especially considering that he had access not only to Josephus, but also to records not available to others? No satisfactory answer has been proposed to this long standing puzzle. Now it appears he had the right year after all.

5.2 December 25

When December 25 was chosen for Christmas, in the fourth century, it coincided with the pagan winter solstice celebration. That is sometimes assumed to be the only reason for the choice, but according to St. Augustine, Christmas was “computed from the twenty-fifth of March — the day on which the Lord is believed to have been conceived, because he also suffered on that same date — to the twenty-fifth of December, the day on which He was born.”[42] Breaking that reasoning down into steps can yield the following traditions, beliefs or assumptions:

- Christ lived a whole number of years.

- Christ died on March 25.

- The length of Christ’s life was reckoned from conception.

- The Julian calendar is implied. Given these premises, one deduces that Christ was conceived on March 25. To this is added one more:

- Christ was born exactly nine months after conception.

If those premises were all correct, then the deduction that Christ was born December 25 would have been valid. The reason for analyzing this logic is that the first premise might be correct, even though the others are probably all false.

| … Christ was born at Passover, but he also died at Passover … an exact number of Jewish lunisolar years. |

This paper proposes that Christ was born at Passover, but he also died at Passover (John 19:14), so Christ could have lived an exact number of Jewish lunisolar years. Thus, Proposition 1 above may have been a correct tradition. In fact, St. Augustine may have quoted that tradition when he once said that Christ was crucified “on the same day in which His mother began to have milk.” [43] Note that this tradition is consistent with Christ’s birth, not his conception, being about the same day as his death.

If the church fathers had known the correct Crucifixion date (April 3, A.D. 33) and had counted back in lunisolar years to the birth (instead of the conception) in 1 B.C., they would have arrived at April 8, 1 B.C. In that case, their reasoning might have led to celebrating Christmas on the correct day.

5.3 January 6

The eastern church put the birth of Christ on January 6, which they said was based on a tradition that Christ was born not on the winter solstice, but twelve days afterward.[44] Note that if these “twelve days of Christmas” had been counted from the spring equinox (March 25) instead, the result would have been April 6.

Duchesne proposed a possible origin of the January 6 tradition. He noted that Sozomen (A.D. 440) mentions that one early Christian sect, the Montanists (c. A.D. 170), celebrated Easter on [the Sunday on or after] April 6.[45] If the eastern fathers counted back as they did in Rome from April 6 (instead of March 25), they would have arrived at April 6 for the conception and January 6 for the birth of Christ. Duchesne’s argument can now be slightly modified: if they had counted back to the birth instead of the conception, the result would have been April 6, in agreement with the conclusion of this study.

6. Conclusion

The principal conclusion is that Herod died in early A.D. 1 because the December 29, 1 B.C. eclipse was the most likely to have been widely observed, and all of the historical evidence can be explained by the one simple hypothesis that Josephus was not aware that Herod’s successors had antedated their reigns. A secondary proposal is that Christ was probably born near Passover, about April 6-9, 1 B.C.

Notes

- Filmer, W.E., “The Chronology of the Reign of Herod the Great,” Jour. of Theo. Stud. 17 (1966), 283-298.

- Barnes, T.D., Jour. of Theo. Stud., 19 (1968), 204-9.

- Ant. XIV.xvi.4 (year specified by the two consuls); XVII.vi.4 (eclipse), XVII.viii.1 (Herod’s death), see also XVII.xiii.2; XVIII.ii.1, iv.6; Wars II.vii.3.

- Luke probably used the usual Roman reckoning, which was that the 15th year of Tiberius began on Jan 1, A.D. 29 (c.f. Tacitus, Annals IV,1). The theory of reckoning from a co-regency of Tiberius is unfounded; it was only suggested to support a 6-5 B.C. birth date for Christ.

- See Barnes; also Bernegger, P.M., “Affirmation of Herod’s Death in 4 B.C.,” Jour. of Theo. Stud., 34 (1983), 526-31; and footnote 28.

- Ant. XVII.vi.5-ix.3; Wars I.xxxiii.5-9.

- Carrying the body on a bier by hand for long distances was not uncommon in royal funerals; the body of Augustus was carried 120 miles by dignitaries (A.D. 14), and Tiberius walked all the way from Germany to Rome with the body of his brother (9 B.C.). See Suetonius, Augustus C.2; Tiberius VII.3.

- Public mournings of national figures were often 30 days (Wars III.ix.5), but the 7-day alternative may have been chosen for both because of the approaching Passover. Mourning was prohibited during Passover (Mishnah Moed Katan 3:5), so if there had not been seven days left before Passover, it would probably have been postponed until afterward, lest the period be shorter than that for Herod, who was hated.

- Martin, Ernest, The Birth of Christ Recalculated (Pasadena, CA: FBR Publications, 1980), summarized in Mosley, John, The Christmas Star (Los Angeles: Griffith Observatory, 1987), and “When Was That Christmas Star?”, The Griffith Observer, Dec. 1980, pp 2-9. See also The Planetarian 9.2, 6-9; 10.1, 14-16; 10.3, 20-23; 11.4, 4-6, and Chronos, Kairos, Christos (Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns, 1989).

- Res Gestae 35; Ovid, Fasti 2.129.

- Ant. XVII.ii.4.

- Orosius, Adv. Pag. VI.22.7, VII.2.16; trans. by Deferrari, R.J. The Fathers of the Church (Washington, D.C.: Catholic U. Press, 1964), vol. 50, p. 281, 287.

- A.U.C. 752 = Augustus’ 42nd year = 2 B.C. (Adv. Pag. VI.22.1, VI.22.5, VII.2.14).

- Schurer, Emil, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ (Edinburgh: T. &T. Clark, 1973), vol. 1, p. 257.

- Ant. XVII.ii.1, XVII.v.2.

- Martin, p. 65-71. Gaius Caesar is sometimes mistakenly listed as governor at this time, but he was heir to the throne of Augustus and had authority to rule all of the eastern provinces, including Syria. (See Schurer, p.259).

- Schaefer, B.E., “Lunar Visibility and the Crucifixion,” Quar. Jour. Royal Astr. Soc. 31, 1990, 53-67.

- Martin, pp. 76-86.

- Ant. XVII.ix.5; Dio lv.9.18-20; Barnes, p. 208.

- Dio lv.10.4, from Cary, E., Dio’s Roman History (Cambridge: Harvard U., 1980).

- An imperial ship could sail to Rome in about a week across the open sea, much faster than merchant vessels, which generally followed the coastline.

- Ant. XVII.i.1, XVII.ii.4, Wars I.xxiii.5.

- Ant. XVII.ii.4-iii.3.

- Meshorer, Y., Ancient Jewish Coinage, (New York: Amphora Books, 1982), vol. 2, p.43. Josephus assigns Philip 37 years, ending in Tiberius’ 20th year (Ant. XVIII.iv.6), which is A.D. 34, implying Philip’s first year probably began in 3 B.C.

- Ant. XVIII.ii.1-2; Wars I.xxxi.1; Suetonius, Augustus LXIII-LXV; Tiberius IV,3.

- Ant. XVII.xiii.1, XVIII.ii.1-2.

- Ant. XIV.xiv.5; XIV.xvi.4.

- Ant. XV.v.2; XV.ix.1-3. Alternate ways of reckoning Jewish regnal years have been proposed (See Filmer; also Edwards, O., “Herodian Chronology,” Palestine Exploration Quar. 114, 1982, 29-42). They do not appear valid because, contrary to Jewish custom at the time, they count a king’s first year as beginning, rather than ending, with the Jewish calendar year following his ascension to the throne. (See Babylonian Talmud, Rosh Hashanah, 2a.)

- Josephus’ age for Herod of 25 in 47 B.C. (Ant. XIV.ix.2; the “15” a calculational or copyist error for “25”) and of nearly 70 at death (Wars I.xxxiii.1), suggest that one was calculated from the other and that Josephus thought Herod died at age 69 in early 3 B.C.

- Hoehner, Harold, Chronological Aspects of the Life of Christ (Grand Rapids: Zondervan, 1977), p. 111.

- Finegan, Jack, Handbook of Biblical Chronology (Princeton: Princeton U. Press, 1964), p. 274.

- This Passover occurred before the ministry described in the synoptic Gospels because John the Baptist had not yet been imprisoned (compare John 3:24, 4:43 to Mat. 4:12, Mark 1:14, and Luke 4:14). If the temple had been completed by the fall of 18 B.C. (Ant. XV.xi.1; XV.xi.6), then spring A.D. 30 would have been 46 1/2 years later (John 2:20).

- Hughes, David, The Star of Bethlehem (New York: Simon &;Schuster, 1979), pp. 106, 103, 108.

- The Julian calendar began on a leap year in 45 B.C., but thereafter leap years were inserted every three years, instead of every four, up to and including 9 B.C. Then the error was corrected by having no leap years in 5 B.C., 1 B.C. and A.D. 4 (Macrobius, Saturnalia I,14,14). Beginning with A.D. 5 the Julian calendar remained unchanged until the Gregorian reform.

- See Mosley (1987), pp. 43-54.

- Calculations for conjunctions and eclipses were done with Lodestar Plus (Zephyr Services) and verified with Z-2-Astronomy (Z2 Computer Solutions).

- Mosley (1980), p. 8.

- Sinnott, Roger, “Thoughts on the Star of Bethlehem,” Sky and Telescope (Dec 1968), 36, 384. He “discovered” this conjunction.

- Martin, p. 16.

- Finegan, pp. 253-4; Wisdom of Solomon 7:2 (in Apocrypha).

- This conjunction occurred about ten months after a similar conjunction on August 12, 3 B.C., suggesting that the first occurred at conception and the second after his birth, but this tempting coincidence does not fit the historical data as well.

- De div. quaest. 1.56, quoted in Lawler, T.C., trans., St. Augustine: Sermons for Christmas and Epiphany (New York: Newman Press, 1952), p. 8.

- Quaest. in Heptad., ii.90., noted in Duchesne, L., Christian Worship (London, 1910), p. 264.

- 13 days counted inclusively. See Finegan, p. 250.

- Sozomen, Hist. Eccel. vii 18,14. See Duchesne, p. 264. Corrections in brackets added by J.P.P.

*The Planetarian is the Journal of the International Planetarium Society. It has published several articles concerning the date of the birth of Christ because the Star of Bethlehem is traditionally the most popular annual planetarium show.